In a church hall transformed for the weekend into a café we ate open sandwiches on dark rye bread and shared wedges of princess cake.

I’ve recently returned from a month in London and Edinburgh. A trip originally planned for 2020 but cancelled because of Covid. So happy to be travelling again. Part of the visit was work-related, and in Scotland my research had a definite culinary focus. Looking into, amongst other things, the provenance of a soup called Cullen skink. Back in London, my friend Jane invited us to the Swedish Christmas Fair in Marylebone. So there we were and there was that princess cake, a light-as-air sponge under a layer of pale green marzipan. Why green? The colour reminded Jane of a children’s story: The Marzipan Man. He was green, she said.

Marzipan men, gingerbread men … why are they always male? Look at their anatomy and they can be any gender. In fact, I like to think there’s something just a little a bit queer about gingerbread men. Is it worth noting that in Cockney rhyming slang ‘ginger beer’ means queer?

Gingerbreads’ origin stories are somewhat opaque, but recipes appear in early medieval cookery manuscripts. English gingerbread began its life as a paste which was used as a medical remedy, later moving to a concoction of breadcrumbs and honey. The Penguin Companion to Food tells me that different parts of the UK have—or had—their own gingerbread specialities. While guilds of gingerbread men (i.e. artisanal producers of gingerbread) emerged in a number of German and Austrian towns.

Australian gingerbread men, my partner insists, are hard-baked and biscuit-like. But the gingerbread texture I recall is softer, halfway between cake and biscuit. A more pliable, lebkuchen-like dough that can be pressed into moulds and fashioned into figures, shapes and even houses. A practice that bakers in Belgium and the Netherlands developed into a fine art.

In First Catch Your Gingerbread, Sam Bilton explores the history of this sweet and spicy treat from ancient times to the twenty-first century. What were those early gingerbreads made from? How did the arrival of treacle—and cheap sugar more generally—change gingerbread recipes? Why did the gingerbread man jump out of the tin?

For a more local account the 2014 book Ginger in Australian Food and Medicine by Leonie Ryder tracks the history and use of ginger in Australia—as both food and medicine—from 1788 to the mid-twentieth century.

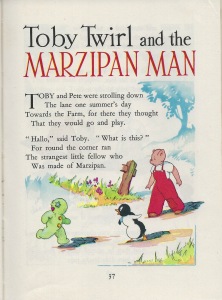

Jane’s remembered Marzipan Man struck a chord. A bit of light Googling and I discovered he appeared in a kids’ book from about 1951: Toby Twirl Tales No 4 (The Sea Wizard; The Marzipan Man) by Sheila Hodgetts. Yes, he is pale green like the Swedish Princess cake. I bought a copy from a second-hand bookshop in South Australia. As well as the eponymous Marzipan Man, the story contains a Toffee Apple Man, some Liquorice Men (described in terms we’d now deem racist), a Chocolate Man, Chocolate Soldiers and a Lollypop Mayor—all male of course, which brings me back to that question: why are they always men?