Chestnuts and winter go together like—well, chestnuts and winter. They also go well with Jerusalem artichokes. Ditto roast meats, bacon, sausages, and most of the brassicas (cabbage, kale, cauliflower, broccoli, bok choy, Brussels sprouts). Not to mention chocolate.

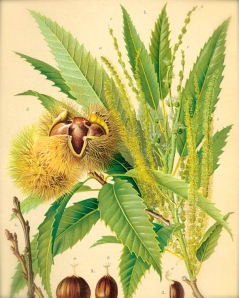

There are several species of sweet chestnut. They all belong to the genus Castanea, but trace their origins to different regions: C. crenata and C. mollissimo come from from China and Japan, C. dentata from North America, C. sativa from Europe and Asia Minor. Unless you’re a grower, that’s probably all the botany you need.

I’ve bought chestnuts hot off braziers in French railway stations and wrapped in cones of newspaper from vendors in Korea. They’re a winter street food, resolutely seasonal, and they taste of the Northern Hemisphere—even if I’m eating them in Sydney.

As kids in England, come autumn we’d amass collections of acorns, beech nuts and conkers. For what purpose, I’m not sure. Certainly not to eat them, they’re all horribly bitter—I know because of course we tasted them, the way children do despite the warnings of grown-ups. I was particularly perplexed by conkers, the fruit (technically the seed) of the majestic horse chestnut tree, because I knew that people did eat chestnuts, and I assumed conkers and chestnuts were one and the same. The only explanation I could come up with was that the people who ate them must be dreadfully poor and unable to afford ‘normal’ food. Now I know that although conkers look like chestnuts and the tree’s common name adds to the confusion, the horse chestnut and the sweet or edible chestnut are not close relatives. The horse chestnut, which produces beautiful spring blossom, abundant summer shade, but nothing remotely edible, is a member of the genus Aesculus.

Horse chestnuts may not have been a source of human nourishment, but their sweet namesakes have a long history as a staple. Before corn arrived from the New World polenta was made with chestnuts. If you can find it, coarse chestnut flour, mixed with regular corn polenta in a ratio of about 1:3, makes a great mash. Goes well with mixed mushrooms or a chunky meat ragù.

Chestnut cultivation has provided fertile ground for environmental historians. A valuable lens through which to analyse the changing patterns of the culture-nature kaleidoscope. If you read French there’s Ariane Bruneton-Governatori’s Le Pain de Bois: Ethnohistoire de la Châtaigne et du Châtaignier. The eponymous wooden bread (le pain de bois) was what peasants in Italy, Corsica, Portugal and elsewhere called the literally flat bread they baked with chestnut flour. Landscape and Change in Early Medieval Italy: Chestnuts, Economy, and Culture by Paolo Squatriti is a microhistory, a different angle on supposedly familiar territory. Here’s an appetiser on Google Books.

If chestnuts and winter go together so do chestnuts and books. John Clare’s poem The Winter’s Come opens with ‘Sweet chestnuts brown, like soleing leather turn’ before proceeding to ‘’Tis Winter! and I love to read in-doors … ’ Over 130 years later, the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, likened books to ripe chestnuts:

And yet the books will be there on the shelves, separate beings,

That appeared once, still wet

As shining chestnuts under a tree in autumn,

And, touched, coddled, began to live

In spite of fires on the horizon, castles blown up,

Tribes on the march, planets in motion. (And Yet the Books, 1986)

French has 2 words for chestnuts (so does Italian, and maybe other European languages too). Châtaigne is the generic term, while marron is reserved for the big, highly cultivated chestnuts that grow singly, one in each nut-case.

From a culinary point of view the big issue with chestnuts is getting them out of their shells and skins. They don’t come with instructions, but the internet is awash with advice and techniques. I soak them in cold water for about 30-40 minutes, score their casings with an X and roast them in the oven for about half an hour. Once cooked, the tough brown husks come off quite easily, but it can be fiddly getting rid of that fine, fibrous undercoat.

Although a few random trees were planted by early settlers, chestnut farming in Australia didn’t get going until after World War II, thanks largely to Italian migrants who were obviously looking to the future. The trees don’t start to bear fruit until they’re at least 15 years old, and don’t reach optimal yield until 50, so you’re thinking ahead, long-term, when you plant C. sativa. Doing it not so much for yourself but for generations to follow.

I’ve blended crushed chestnuts with icing sugar then mixed it up with broken meringue, whipped cream and grated chocolate to make a dessert that’s Mont Blanc meets Eaton mess. On the savoury front, a classic comfort dish is the Korean kalbi or galbi jjim or tchim. In Hangul it’s 갈비찜 and it’s a rich, mellow stew of marinated beef-on-the-bone (traditionally short ribs, but I’ve also made it with veal shanks), slow-cooked with carrots, onion, daikon or Korean radish, mushrooms, a nashi pear—and chestnuts. It’s one of those flexible recipes that’s hard to stuff up and people adapt every which way. Throw ‘galbi jjim’ into YouTube and check out the cooking demos.

Oh this is great! Appetizing and comforting, just like the nut itself. French bakers still sell bread made with chestnut flour, but only at Christmas sadly. Every year I always pick up the first conker I see – then I know it is definitely Autumn.